Photo’s Joanne Hutchinson

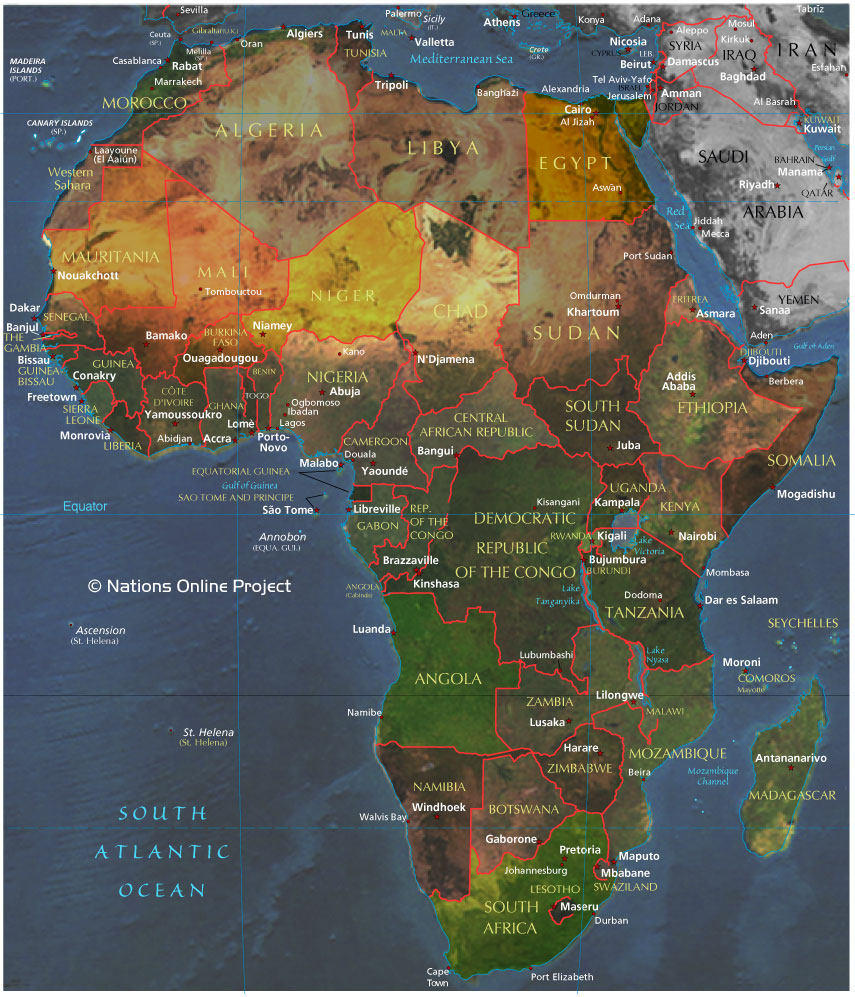

Part of a conversation from Linkedin- Is Africa ready to Landscape Agriculture?

Non Executive Director at SSA Energy Independence Association

Farmers and rural villagers in Africa is not to blame for deforestation.

They do not cut down trees by the millions.

Urban wood and charcoal merchants play a huge part in deforestation.

Foreign hardwood buyers and their local agents harvest forests unsustainable.

Large commercial forestry and palm oil operators are responsible for lots of deforestation.

Agroforestry (evergreen agriculture) is normal practice in African agriculture, unless it is a commercial / mechanized farm (usually established by a foreigner)

Pieter while I agree with you, forests have been and probably will continue to be a cheap source of fuel (firewood or Charcoal). The problem has been tree planting has not matched consumption. Additionally, urbanization and population growth are encouraging encroachment on reserves. Further, the only value attached to forests is timber and actually forests are being cleared to make room for agriculture. However, no impact studies have been exhaustive in terms of ecosystem disruptions and long-term negative impact on agriculture. In summary, arable land management seems an enduring problem in Africa.Naturally self re-generating forests, and traditional agro-forests, are sustainable, but trees planted into areas where that species has been absent for some time might lack the myccorhiza and other soil fauna and flora necessary for them to thrive. Later the lack of natural pollinators and seed dispersal fauna may be a problem. Trees grown in established woodland may find protection from pests and diseases, by the dilution effect of their neighbours, by the presence of beneficial organisms, and by the group chemical defences of woodland trees. Trees planted outside established woodland areas lack these advantages.

Babigumira, the traditional clearing of small plots of forest for agriculture did very little, if any lasting damage.

Harvesting of dead trees for firewood also not a problem.

Commercialized harvesting of firewood and charcoal is a serious threat.

Here is a small example: We have a small city called Soweto. All the buildings have electricity connections. The residents still burn 30,000 tons of wood per year. An investigation by the government found this wood is sourced from the rural areas, much of it protected trees.

There are also several companies exporting charcoal for profits.

Despite all the studies showing the negative effects of deforestation, very little has changed

The majority of tree planting is for commercial forestry and will be cut down in 6 – 25 years.

Trees have commonly formed an important part of Africa’s traditional farming systems. In the bush-fallow, slash-and-burn cultivation systems, farmers exploited the potential of trees and shrubs for soil fertility regeneration and weed suppression during the fallow phase and widely used them as source for staking material later during cultivation. Trees and shrubs are also widely grown in cropped areas particularly in compound farms. They are mainly used for soil fertility maintenance and as auxiliary sources of food, fodder, fuelwood and for other domestic needs.

B.T. Kang, Soil Scientist, International Institute of Tropical Agriculture, Ibadan, NigeriaTrying to establish new areas of woodland makes no ecological sense if we are not primarily protecting established woodland. New woodland planting should be planted adjacent to old protected woodland, or traditional agroforestry areas, and on a proportional scale to the old woodland, if it is to succede.

Pieter

The use by farmers of trees that provide shade or hedges to retain livestock, or to protect banks or ditches that help prevent erosion, usually depends on locally common species. Novel species when introduced in these situations (especially in hedges) generally fail to thrive and are swamped by more vigorous local species, though the novel species may establish properly after many human generations have continued the effort. (In the UK the rule of thumb is 1 new species per 500m of hedge per 100 years.)

Pieter